Vermicomposting Worms UK

Section 4 of the Vermicomposting: Complete Guide

L.J.

Environmental Advocate

Contents

Let’s Take a Moment to Think About Worms

They’re easy to overlook—no feathers, no flowers, no fanfare. But worms are quietly working beneath our feet, shaping the very ground we grow from. These humble creatures are essential to life above the soil, playing a role so vital it’s hard to overstate.

Before we zoom in on composting worms, let’s take a moment to appreciate earthworms in general—the unsung heroes of healthy ecosystems.

🔧 Earthworms are ecosystem engineers.

Quietly tunnelling through the earth, they aerate the soil, recycle nutrients, and build the perfect environment for plants and animals to thrive. They are hugely underappreciated—possibly because they do their work underground. Their castings are jam-packed with nutrients that are easily accessed by plant species.

Across fields, forests, and gardens, earthworms help:

- 🕳️ Improve soil structure by tunnelling channels for air and water

- 🍂 Break down organic matter into plant-available nutrients

- 🦠 Support biodiversity by feeding microbes and enriching ecosystems

- 🌧️ Reduce erosion by binding soil particles together

- ⚗️ Process heavy metals by absorbing and transforming contaminants into less harmful forms—helping remediate polluted soils and compost

🪱 Choosing Your Composting Crew

When it comes to worm composting, not all species behave the same—and not all names mean what you think. Some worms are speedy eaters, others are tough and weather-hardy. But before you pick your composting crew, it’s worth untangling the naming muddle.

In the UK, composting worms are often sold under overlapping labels like “tiger worms,” “red worms,” or “compost worms.” These names can refer to different species—or sometimes the same one. Suppliers may mix Eisenia fetida, Eisenia andrei, and Dendrobaena veneta under a single name, while garden earthworms like lob worms (Lumbricus terrestris) sneak into the conversation despite being unsuitable for bins.

This section clears up the confusion so you can choose the right worms for your setup, climate, and composting goals—with confidence.

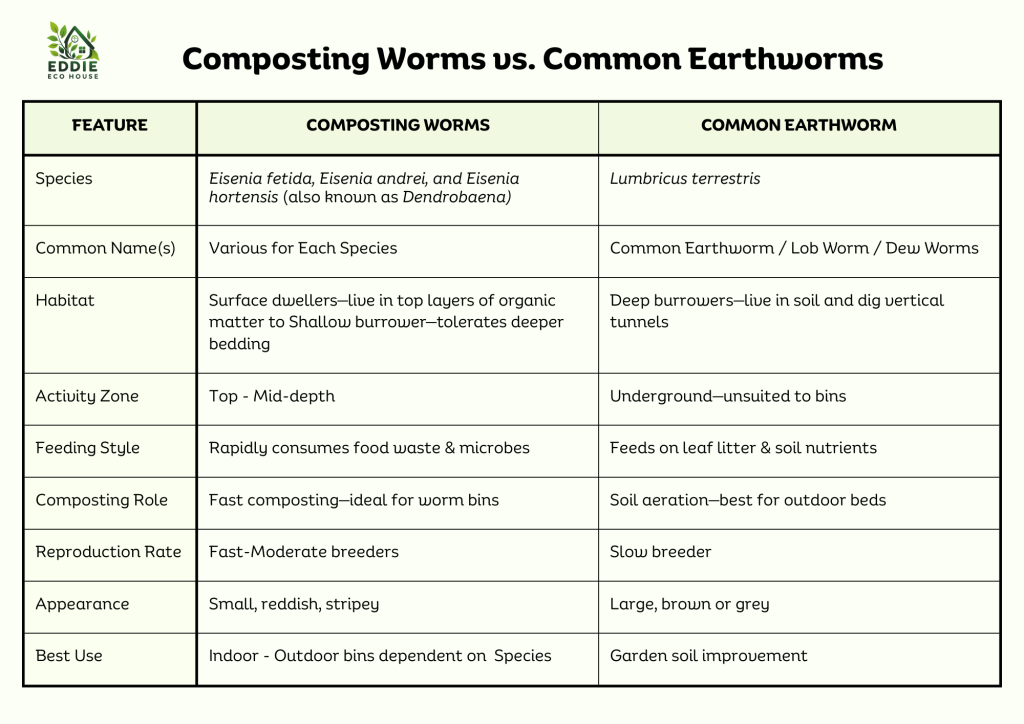

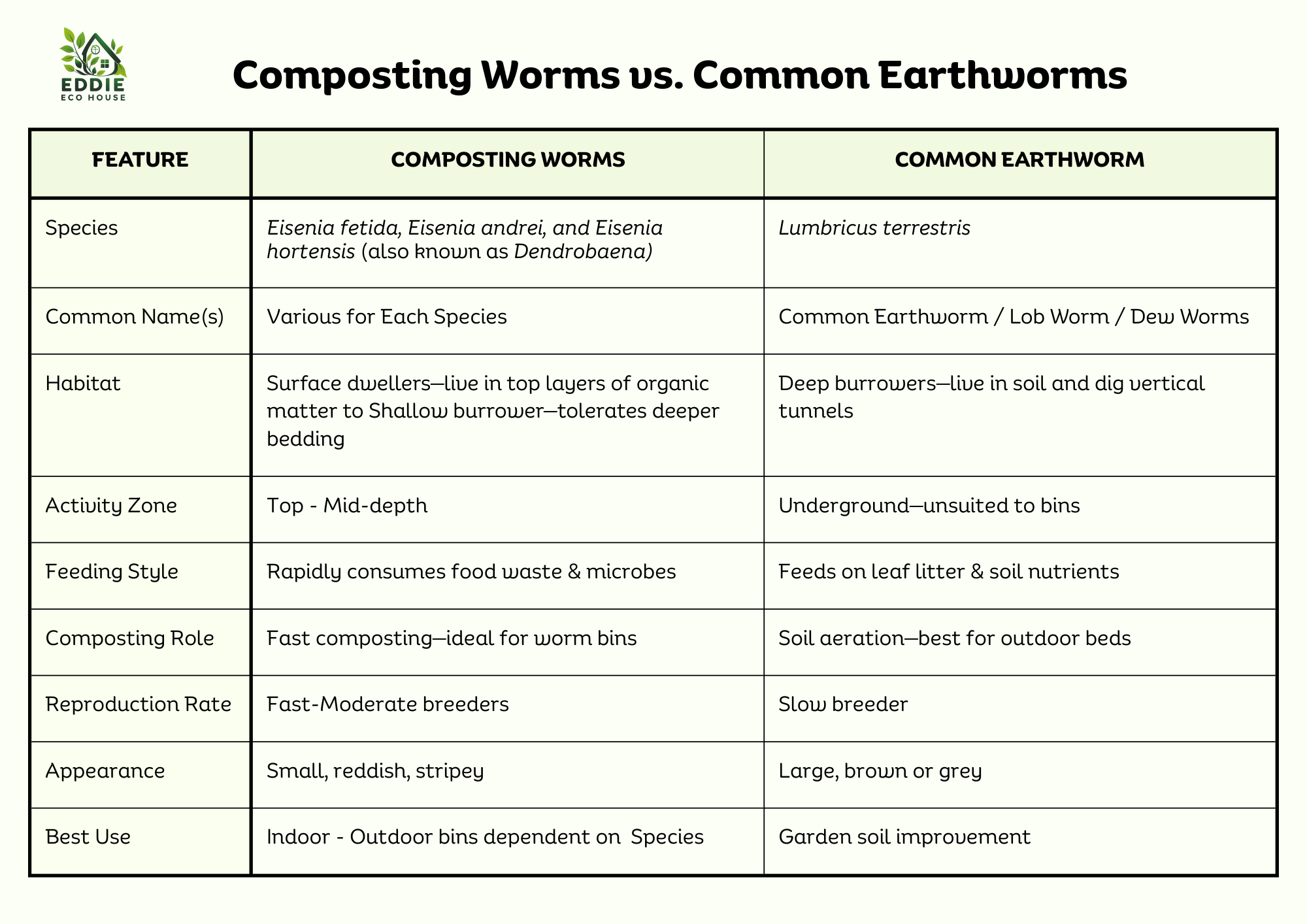

🪱 Composting Worms vs Common Earthworms: What’s the Difference?

Let’s start by separating the true composting champions from their garden cousins.

Composting worms are surface dwellers that thrive in moist, oxygen-rich environments with regular feeding. They live in the top layers of soil or bedding and excel at breaking down organic waste.

In contrast, common earthworms like Lumbricus terrestris (lob worms) prefer deep burrows and cooler, undisturbed soil. They’re vital for garden ecosystems—but unsuitable for worm bins.

🚫 Avoid buying packs of worms that list common earthworms for your vermicomposting system.

Specialist Composting Worms

Specialist Composting Worms

Some worms prefer the rich, messy top layers of decaying organic matter- and that’s where composting worms shine.

Specialist Composting Worm Species:

- Eisenia fetida

- Eisenia andrei

- Eisenia hortensis / Dendrobaena veneta

Unlike their Earthworm cousins, these composting worms:

- ♻ Thrive in worm bins, compost heaps, and upcycled containers.

- 🛏 Prefer moist, well-ventiliated bedding over compacted soil.

- 🍽 Reproduce quickly and consume up to half their body weight daily.

- 🌱Create large volumes of worm castings with more concentrated nutrients and microbial activity due to diet of fresh organic matter.

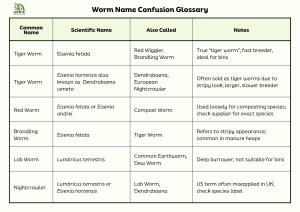

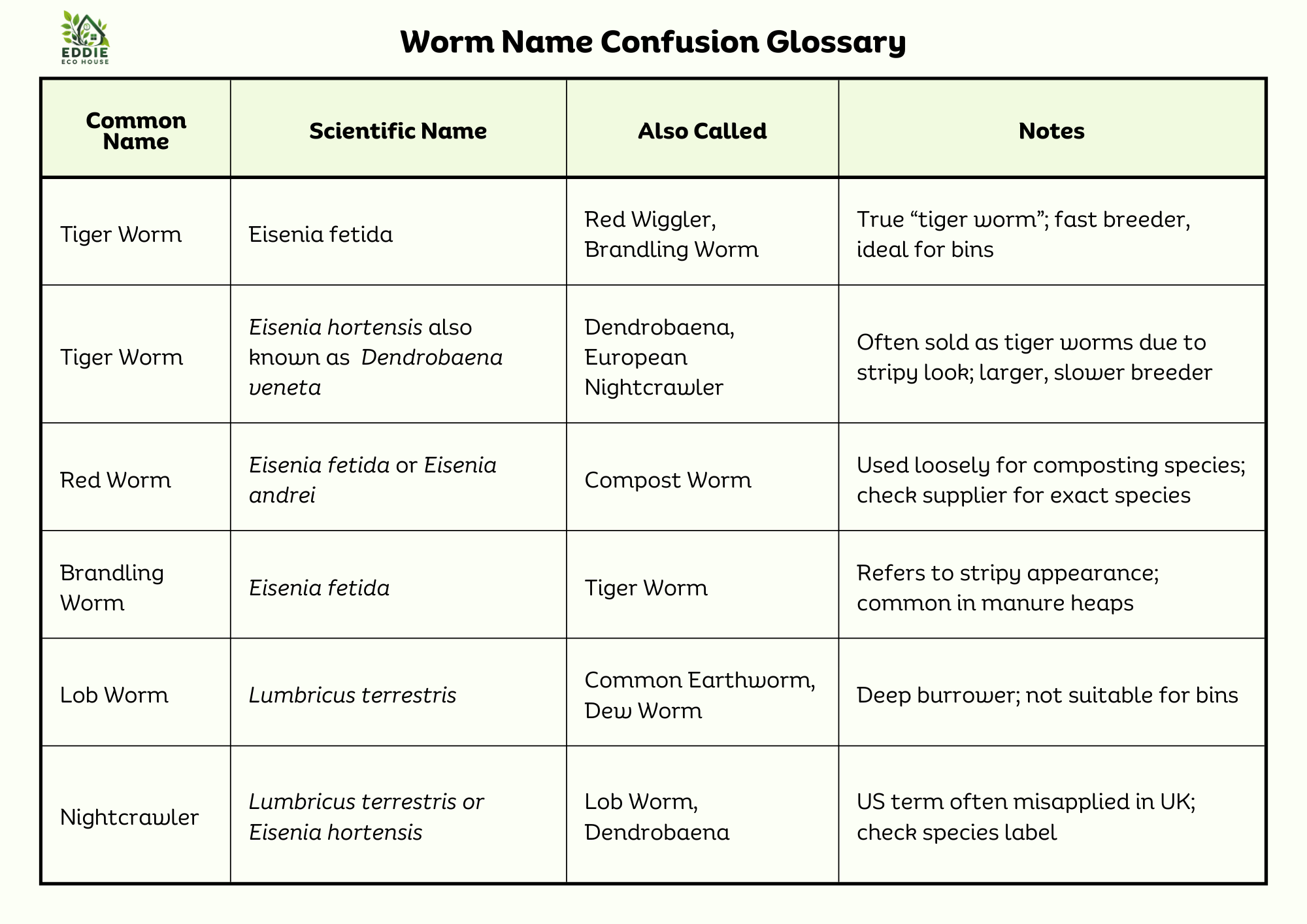

🪱 Worm Name Confusion: What’s in a Name?

Composting worms often go by multiple names—scientific and common—that can vary by region, supplier, or even bin setup. From red wigglers to tiger worms, the overlap can be confusing, especially when species like Eisenia fetida, Eisenia andrei, and Dendrobaena veneta share similar traits but differ in size, breeding speed, and habitat preferences.

This glossary clears up the mix-ups so you can choose the right worms with confidence.

Eisenia fetida

Worm Naming Confusion: Eisenia fetida = Red Wiggler, Tiger Worm, Brandling Worm

You’ll notice Eisenia fetida appears under several aliases, reflecting its popularity and versatility across composting setups.

- Red Wiggler is the most widely used name in global vermicomposting guides

- Tiger Worm refers to their distinctive striped appearance

- Brandling Worm is a traditional UK term, often used by anglers and gardeners

Eisenia hortensis / Dendroabaena veneta

🔬 Scientific Name Confusion: Dendrobaena veneta vs. Eisenia hortensis

In UK composting and bait circles, Dendrobaena veneta is the preferred scientific name for the European Nightcrawler. However, some suppliers—especially international ones—still use the older name Eisenia hortensis.

✅ Both names refer to the same species

✅ Behaviour, composting ability, and care requirements are identical

🧬 Naming differences stem from historical classification and regional usage

When buying worms, check the Latin name or ask suppliers directly—especially if you’re sourcing from abroad or mixing species.

Dendroabaena veneta

🐛 Common Name Confusion: European Nightcrawler, Dendrobaena, Compost Worm

Just like scientific names, common names for Dendrobaena veneta vary depending on context:

- European Nightcrawler – Most common in US composting guides and forums

- Dendrobaena – Widely used in the UK, especially by bait suppliers and composting retailers

- Compost Worm – A generic label that may refer to Dendrobaena veneta, Eisenia fetida, or a mix of species

These names are often used interchangeably, but they don’t always guarantee the same species. If you’re buying worms for composting, especially online or from bait shops, it’s best to confirm the Latin name to ensure you’re getting the right composting crew

Eisenia andrei

🪱 Common Name Confusion: Red Worm, Compost Worm

- Red Worm – Often used for both Eisenia fetida and Eisenia andrei

- Compost Worm – A generic label that may include either species or a mix

These names are often used interchangeably with Eisenia fetida, especially by suppliers who sell mixed tubs. Because they look and behave similarly, most composters treat them as functionally equivalent—though E. andrei tends to have darker, more uniform colouring.

Understanding these aliases helps you avoid confusion and choose worms that suit your bin type, climate, and composting goals.

Rather than memorising every name, focus on the scientific (Latin) names listed in the comparison table—they’re the most reliable way to identify species across suppliers, regions, and composting setups.

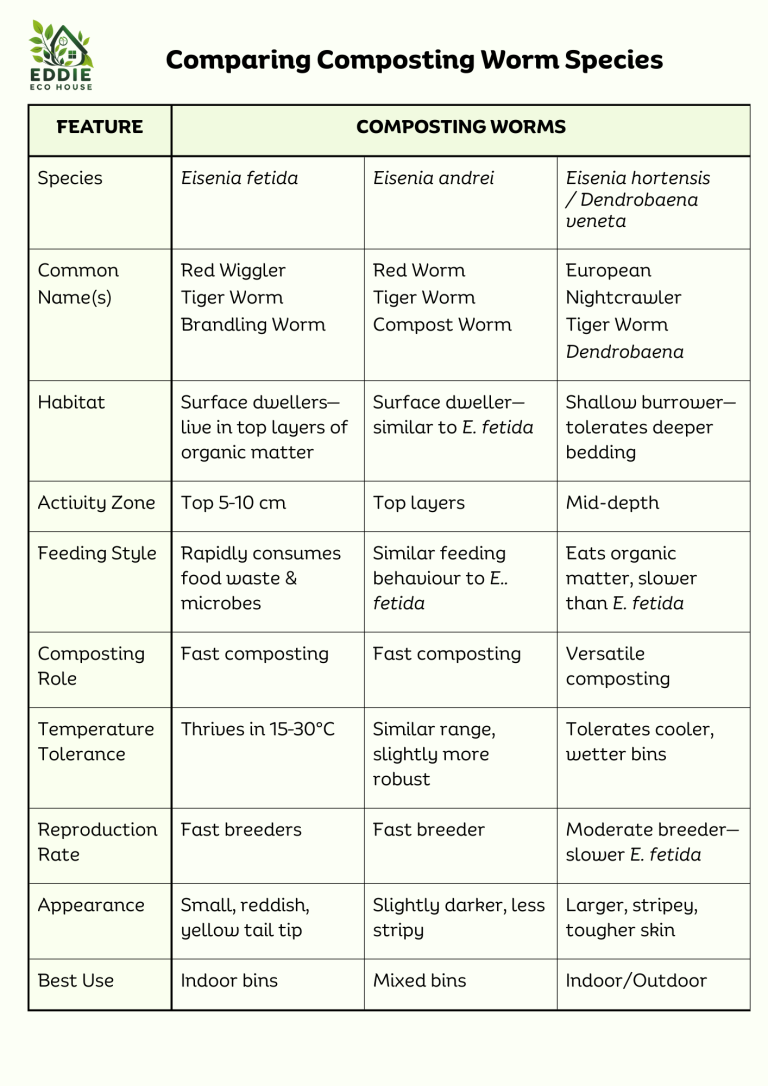

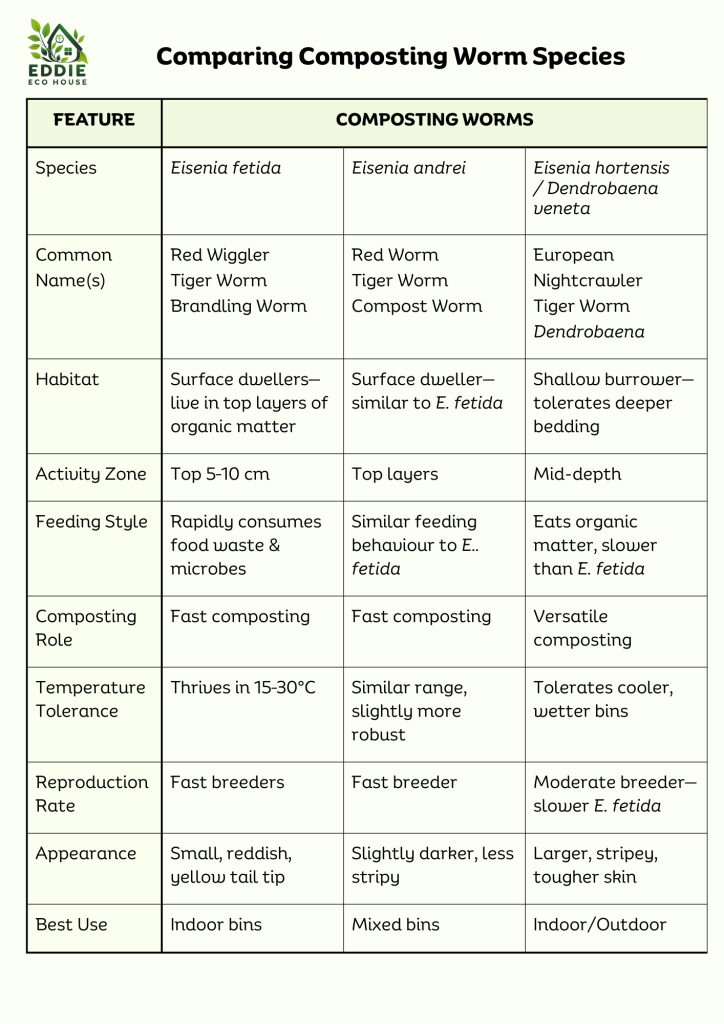

🪱 Comparing Composting Worm Species

Now that we’ve untangled the naming muddle and met the main composting contenders, it’s time to compare them side by side. Each species has its own strengths—whether it’s speed, resilience, or suitability for UK climates and bin types.

The table below highlights key differences in appearance, behaviour, and composting performance to help you choose the best fit for your setup. Whether you’re starting a classroom wormery or scaling up a garden bin, understanding these traits makes selection easier and more effective

🪱 Key Differences between Composting Worms

Eisenia fetida

- Appearance: Small, reddish-brown with pale stripes between segments

- Best for: Indoor Bins with shallow trays.

- Tip: E. fetida is the most stripey and commonly used in Vermicomposters.

Eisenia andrei

It’s a close relative of Eisenia fetida—similar in size, behaviour, and composting ability—but with a few subtle differences.

- Appearance: Small, solid reddish-brown; slightly darker and less stripey than E. fetida

- Best for: Performs just as well in Indoor Bins with shallow trays

- Tip: Often included in mixed packs without separate labelling

While not always distinguished from Eisenia fetida, it’s a perfectly effective composting worm and thrives in the same conditions.

Eisenia hortensis / Dendrobaena veneta

- Appearance: Small, reddish-brown with pale stripes between segments

- Best for: Outdoor bins or bins with deeper trays.

- Tip: D. veneta is chunkier and more robust- ideal for the UK climate.

Why Use a Mix of Composting Worms?

Many UK suppliers offer mixed packs of Eisenia fetida and Eisenia andrei, or combine with Dendrobaena.

This blended colony gives you the best of both worlds—fast composting, climate resilience, and bin stability.

🌡️ Climate Resilience

Different species tolerate temperature shifts differently.

- Dendrobaena veneta is more cold-hardy—ideal for outdoor bins or unheated sheds

- Eisenia fetida and E. andrei thrive in stable indoor conditions

A mix helps your bin stay active year-round, even in British winters.

🍽️ Feeding Diversity

Worms have slightly different feeding rates and preferences.

- E. fetida is a speedy eater and reproduces quickly

- D. veneta is slower but handles tougher scraps and bedding

Together, they tackle a broader range of food waste and bedding textures.

🧬 Bin Stability

Mixed species can balance each other out.

- If one species slows down due to temperature or pH, others may stay active

- Diversity can reduce the risk of population crashes or bin imbalances

🪴 Supplier Practicality

Many UK suppliers sell mixed tubs by default.

- It’s easier to harvest and ship a blend

- Labels like “compost worms” or “red worms” often include E. fetida, andrei, and Dendrobaena

🪱 Note: Although worms are often sold in mixes, you can buy specific species—see our worm purchasing comparison, in Section 2, for supplier guidance.

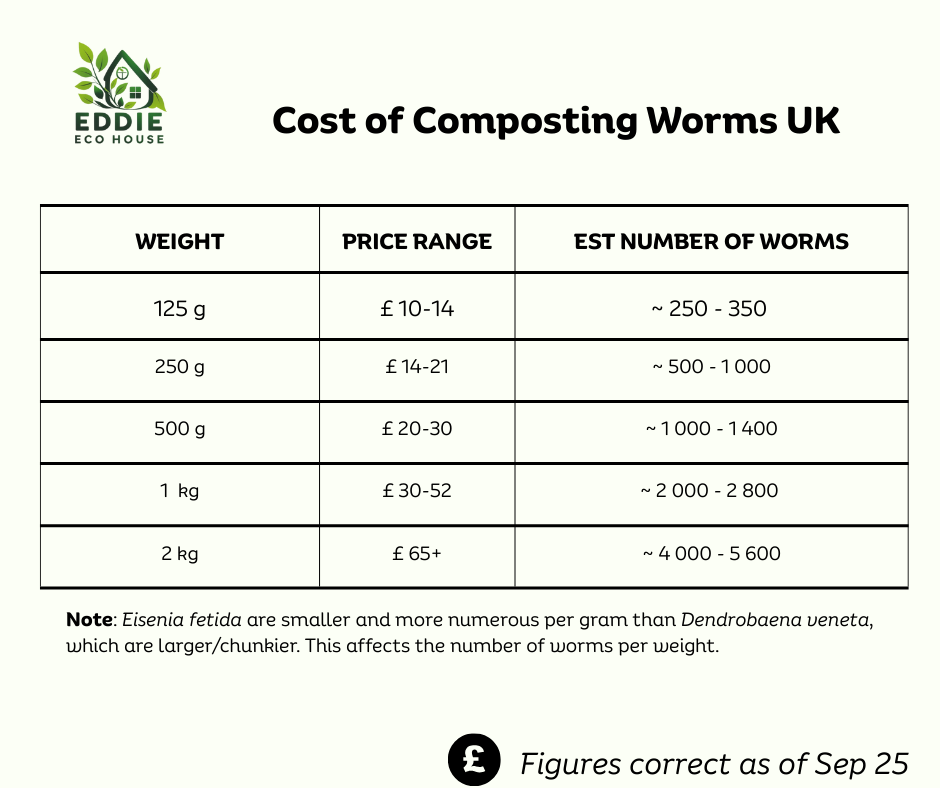

🪱 How Many Worms For Your Bin?

As we discussed in Section 2, the number of worms you need depends on the size of your worm bin and your composting goals—whether you’re aiming for slow, steady breakdown or rapid waste processing. In this section, we’ll explore the reasoning behind worm quantity, feeding capacity, and how to scale your setup over time.

Worms are typically sold by weight:

- 100g → Suitable for small bins (10–20L)

- 250–500g → Ideal for most home setups

- 1kg+ → Recommended for large bins or community projects

Worm Feeding Capacity

Composting worms can eat around half their body weight per day in ideal conditions. This means 500g of worms can process roughly 250g of food scraps every day once your bin is established.

Start Small

It’s best to begin with fewer worms and let the population grow naturally. Adding too many at once can overwhelm the system and lead to escapes. Under the right conditions, worm populations can double every few months.

🪱 Worms: What Makes Them Composting Champions

Worm Anatomy: Inside and Out

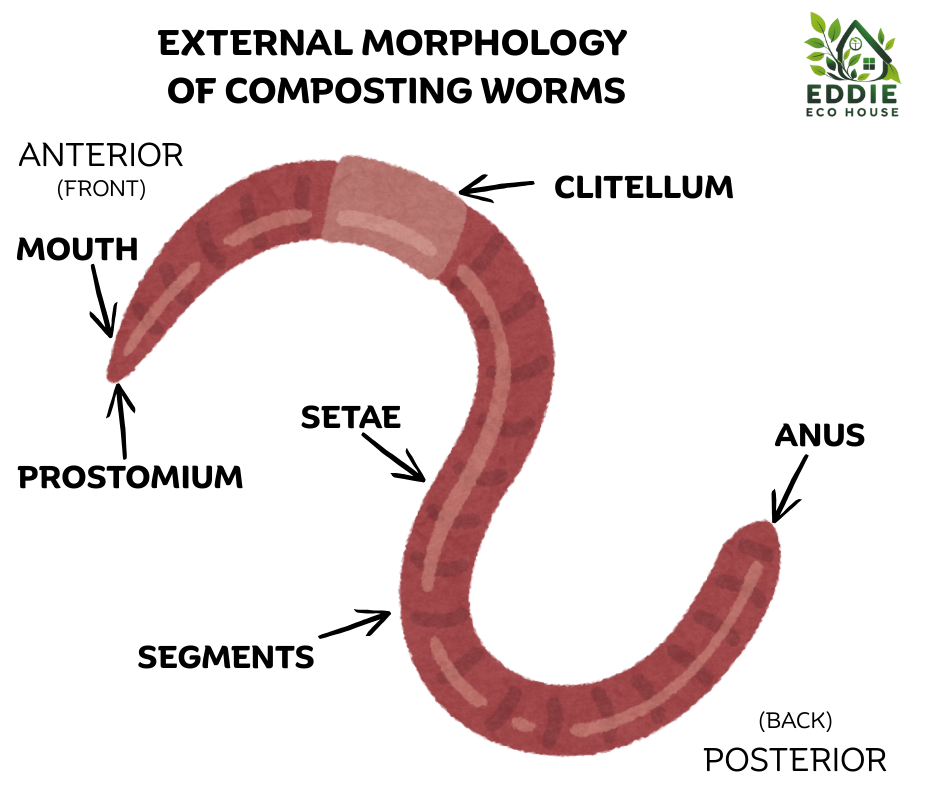

Worms may seem simple, but their bodies are full of specialised structures that help them move, feed, and recycle organic waste. In this section, we’ll explore their anatomy—both outside and in.

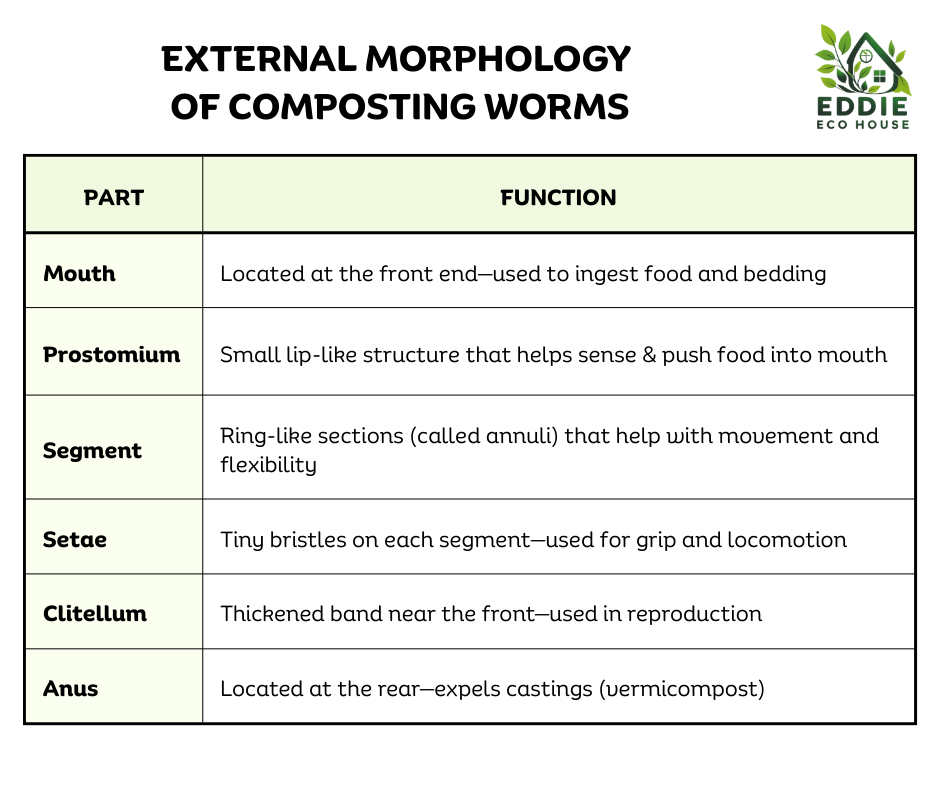

We’ll start with external morphology, which means the visible features of a worm’s body—like its segments, bristles, and clitellum band. These parts help worms sense their surroundings, wriggle through bedding, and reproduce.

Then we’ll look at the digestive system, tracing the internal journey of food from mouth to anus. Each organ plays a role in breaking down scraps and turning them into nutrient-rich castings that support healthy soil.

Together, these systems show how worms are perfectly adapted for life in compost bins—and why they’re such powerful allies in sustainable living.

🪱 External Morphology: What You Can See (and Why It Matters)

The Outside of the Worm

At the front end, the prostomium acts like a lip, guiding food into the mouth. Near the head, you’ll spot the clitellum—a thick band used in reproduction. At the rear, the anus expels nutrient-rich castings.

Together, these external features allow worms to sense their environment, move efficiently, and process organic waste.

To help visualise these features, the diagram below highlights key parts of a composting worm’s body, from head to tail. Each label corresponds to a function—whether it’s movement, feeding, or reproduction. The accompanying table breaks down what each part does, making it easier to understand how worms interact with their environment and support composting.

Worm Facts

- Worms have no eyes, but they sense light and vibration

- They breathe through their skin—so moisture matters

- One worm can produce several cocoons per week, each with 1–5 baby worms

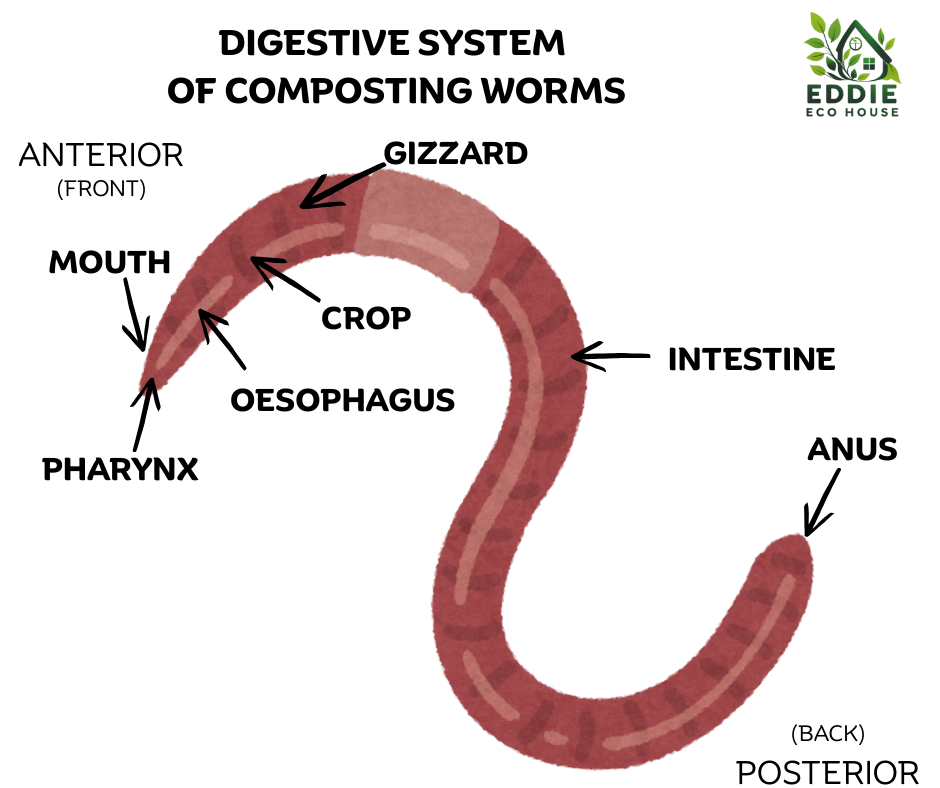

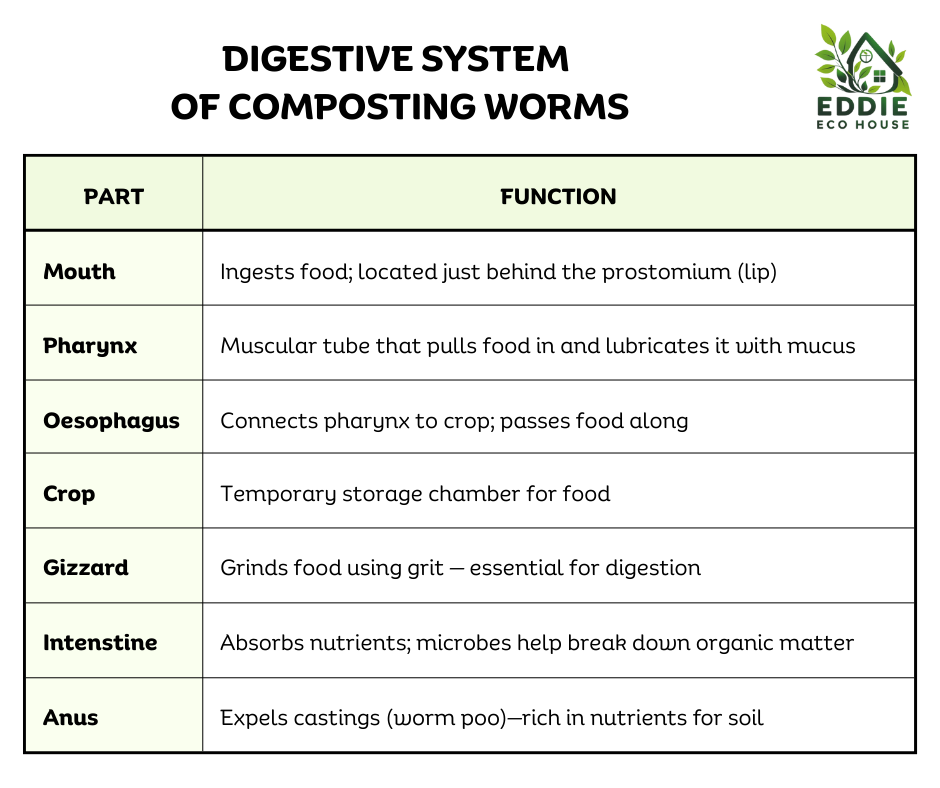

🧪 Digestive System: How Worms Turn Scraps into Soil Gold

Worms may be small, but their digestive system is a powerhouse of natural recycling. From the moment a scrap enters the mouth to the final castings expelled from the tail end, each part plays a vital role in breaking down organic matter and enriching the soil.

Below, we follow the food’s journey through each part of the worm’s digestive system.

🧪 Inside the Worm

Food enters through the mouth, where it’s drawn in by muscular action. The pharynx helps pull food in and coats it with mucus to aid movement. From there, it travels down the oesophagus into the crop, a temporary storage chamber.

Next, the food reaches the gizzard, where it’s ground up using grit like crushed eggshells. The broken-down material moves into the intestine, where nutrients are absorbed with help from microbes. Finally, waste exits through the anus as castings—nutrient-rich compost for your garden.

Together, these internal organs transform kitchen scraps into soil-building gold, making worms essential allies in sustainable living.

Note: To help worms grind their food efficiently in the gizzard, adding small amounts of grit—such as crushed eggshells or horticultural grit—can be beneficial. We’ll cover worm-safe food grits in detail in Section 5: Feeding Your Vermicomposter, and explore additional optional extras like rock dust in Section 8.

To show how food travels through a worm’s body, the diagram below maps each part of the digestive system—from mouth to anus. You’ll see where scraps are stored, ground, absorbed, and transformed into castings. The table alongside explains what each organ does, making it easy to understand how worms turn waste into soil-enriching compost.

Worm Facts

- Worms have no teeth—they rely on their gizzard to grind food using grit like crushed eggshells or soil particles.

- The intestine runs nearly the full length of the worm’s body and absorbs nutrients with help from microbes.

- Worms can digest food within 24–48 hours, depending on temperature, moisture, and food type.

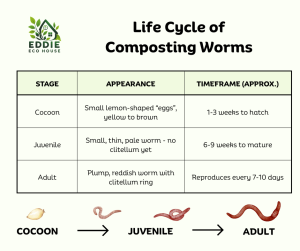

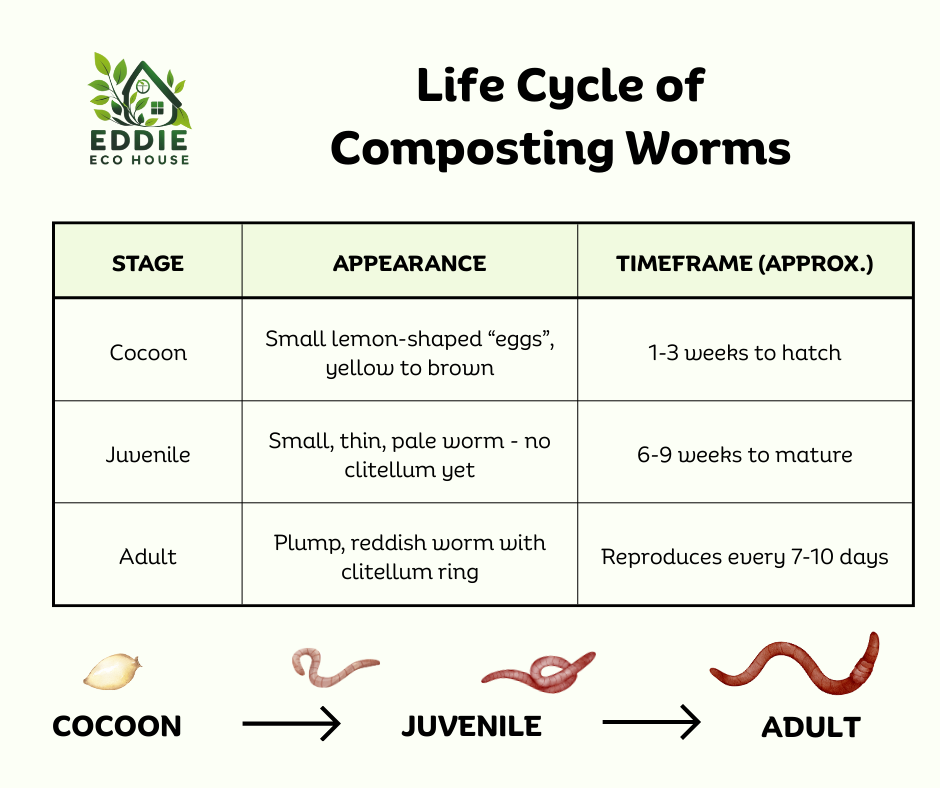

🪱 Lifecycle & Population Growth in Your Wormery

Understanding and recognising the different life stages of worms and their reproductive process equips you to maintain a healthy, balanced worm bin that efficiently transforms waste into nutrient-rich compost, keeping your vermicomposting thriving.

🔄 Worm Reproduction Basics

Most composting worms are hermaphrodites, meaning each worm has both male and female reproductive organs.

While they don’t have separate sexes, two worms are still needed to reproduce. After mating, each worm produces cocoons containing fertilised eggs—typically 2 to 5 per cocoon. In a healthy worm bin, this leads to steady, efficient population growth over time.

🥚 Cocoon to Worm

In a healthy worm bin, reproduction happens naturally as worms lay tiny lemon-shaped cocoons.

These cocoons hatch into 2–5 baby worms each, steadily growing your population over time. The hatchlings emerge as small, thin, pale worms and grow through their juvenile stage, becoming progressively redder. As they mature, they develop a clitellum—a thickened ring that signals adulthood and reproductive capability.

✅ Supporting Natural Worm Reproduction in Your Wormery

To keep your worm bin healthy and reproducing naturally, maintain stable conditions:

- Maintain stable conditions for moisture, bedding, and airflow as covered in Section 6: Setting Up Your Bin.

- Feed moderate, worm-safe scraps detailed in Section 5: Feeding Your Vermicomposter.

- Handle castings gently to protect cocoons—see Section 7: Harvesting Castings.

- Adding grit like crushed eggshells supports digestion (also in Section 5).

- Optional extras like rock dust are covered in Section 8.

With the right care, your worm bin will maintain and even expand its population—no need to keep buying worms.

Now that you know all about your composting crew, it’s time to feed them right. Section 5 breaks down which foods to add, which to avoid, and how to keep your worm bin balanced for healthy, efficient composting.

Affiliate Disclosure: To keep this guide free and accessible, I use affiliate links where appropriate. If you make a purchase, I may earn a small commission—never influencing the price you pay. Every recommendation is based on hands-on experience or thorough research tailored to UK composting needs.